A few months back, I wrote about how Vision Zero became mainstream in Sweden. This week, I want to introduce another road safety approach. This one has been put into action just across the North Sea - the Dutch Sustainable Safety approach.

While the Swedish approach had tended to concentrate on drivers and motor vehicles (developing to include those outside of vehicles more recently), the Dutch approach to Sustainable Safety is more developed and encompassing that the Swedish approach. Please note that this post is my understanding and if you know better or disagree, please do comment.

"Sustainable Safety" is probably an odd name because I'd imagine many people would be thinking about it being environmentally friendly. There is a link, but it has nothing to do with the natural environment. The 1987 Brundtland Report ”Our Sustainable Futures” defined sustainable development as;

”development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”

The use of "sustainable" in "sustainable safety" is therefore describing the designing out of road safety problems today so that users aren’t exposed to the same problems in the future. This applies equally to new schemes as well as retrofitting existing streets and roads.

The 2009 CROW Road Safety Manual states;

“The road traffic system is inherently unsafe: the design of the current system is such that it causes accidents and serious injuries. The inherent road unsafety and the fact that this notion should be the starting point for improving safety is inspired mainly by developments in other sectors, such as aviation and the process industry, where this awareness had dawned much earlier. In short: Sustainable Safety replaces the accepted curative approach to unsafe locations by a proactive and preventive approach.”

In fact, the manual can be downloaded from Road Safety for All website (first link). Lots of people talk about the CROW Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic, but the road safety manual really gets under the skin of the Dutch approach. You'll see familiar topics such as infrastructure, vehicle design, education and enforcement.

The original vision for sustainable safety was published in 1992 which surprised me given I had read about things like De Kindermoord and the oil crisis from the 1970s. This film by Mark Wagenbuur sets the scene in explaining the fall and rise of Dutch cycling and the modern push for infrastructure in the 1970s. Sustainable safety as an approach was already being implemented so maybe the vision can be seen as a consolidation of the 20 years of learning that had already taken place.

The origin was quite similar to Vision Zero in that it was about looking at what went wrong, changing it and if collisions did occur, that their severity would be reduced. The third version of the vision covers 2018 to 2030 and sets out the five principles of sustainable safety;

- Functionality of roads,

- Bio(mechanics): minimising differences in speed, direction, mass and size whilst maximising protection for the road user,

- Psychologics: aligning the design of the road traffic environment and road user competencies,

- Effectively allocating responsibility,

- Learning and innovating in the traffic system

The first three are design principles and the last two are organisational principles.

Functionality seeks to design road sections and intersections which only have one function for all modes of transport (also called mono-functionality), either a traffic flow function or an exchange function. Traffic flow is as you'd expect, but "exchange" is simply about stuff happening such as junctions, parking, crossing the street etc. It has parallels with the UK "movement" and "place" approach, except the Dutch actually decide what a road or a street is for rather than the often seen UK fudge of trying to accommodate all functions and failing.

Functionality has seen the Dutch highway system stratified into three types of highway;

- Through roads which perform a movement function along roads and through intersections;

- Distributor roads which perform a movement function along roads, but an exchange function at intersections;

- Access roads which perform an exchange function along roads and intersections.

Through roads are motorways and large roads (such as trunk roads and arterials) which are developed to provide a movement function without exchange. Motorways can technically be looked at as a separate class of road, although sometimes of course, cycle tracks cross motorways or run parallel to them to cross barriers such as rivers. Some large roads carry enough traffic to be through roads and so the provision of walking and cycling infrastructure will be to a high standard of protection.

Where they share the same space, they will often be grade separated such as in the photograph below where the cycle track is taken under the large grade separated junction ahead.

Distributor roads connect through roads to access roads. They can have walking and cycling provision, but it must be separated from motor traffic. When exchanges need to happen, then these will usually be at intersections. An intersection type can take all sorts of forms such as traffic signals, roundabouts or even the wonderfully named "voorrangsplein" or "priority square". The photograph below is an urban signalised crossroads on a distributor road.

The difference between distributors and through roads can sometimes be difficult to see and things can change over time. The photograph above is on an arterial route into Amsterdam but it doesn't traverse the city and so it's not providing a through function. There are side streets accessing this road directly and it connects to other distributors at signalised junctions; it also carries tram and bus routes. The important thing, however is that the volume and speed of traffic is such that people walking and cycling are protected. Roads can of course change type along their length as uses and needs change.

Access roads have everything going on. They are where people live and they may have local shops and services. There may be a footway provided for walking, but they don't have specific cycling infrastructure. The photograph below is an access road. People can park, they cross the road, there might be deliveries going on - it's clearly a place intended for people rather than through traffic.

Access roads can be created by retrofitting modal filters and by the use of local one-way systems so that the only people needing to take a motor vehicle into them either live there or are visiting for a specific reason. The photograph below shows a simple modal filter.

It's also common to find access roads running in parallel to the other two types of roads with managed connections. This can be seen in built up areas where there is a local parade of shops which allows the exchange activity to be conducted off the main road or in rural areas where the access road provides utility for farmers and cycle routes where traffic volumes are low.

The Dutch have a national policy approach to classify each road or street within this framework and to deploy a strategy to get there if conditions don't already dictate the type. It's a network-level issue because in general, there is a hierarchy to follow. For example, access roads should not connect to through roads and if they do, then there will be a long term plan to unravel the network to change this.

It's also worth mentioning that this is primarily looking at how motor traffic is managed and so walking and cycling networks will be developed separately with the road classification issue coming into play where there are exchanges. It's also why a main cycle route may be developed on access streets because it allows cycle traffic to dominate traffic, the latter simply being allow access. Sustainable safety still applies, however, because there is a speed differential between people walking and cycling - if there's no footways, then street isn't suitable for a main cycle route.

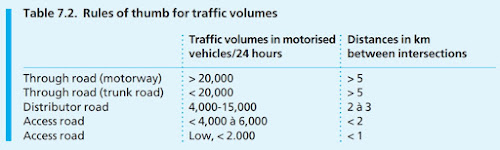

The Road Safety Manual has a table which provides a rule of thumb for the difference in motor traffic flows for the road types. It is not intended to be a specific measure, just a way of getting an initial feel for the situation;

It's worth considering the fact that some locations can have high flows at peak times which might require other design decisions. It could be that a through road has a high proportion of local traffic and for through traffic, there is a parallel route which is better suited to take it. Engineering controls at a network level could therefore be used to change the road from a through road to a distributor road.

Where a road or a street cannot be classified at the network level or if the intended use isn't reflected by the design, then it will be designated a "grey road". This is recognition that it's not possible to do everything at once, although there will often be interim measures deployed aimed at protecting the most vulnerable person in the system. This tends to be an urban issue where there is a flow function competing with an access function and where there isn't space at the moment to provide protection to become a proper distributor.

The street may access road in the future because of network changes elsewhere or by some significant redevelopment, but until this happens, measures are deployed to provide protection. So you may see measures deployed to make the street look and feel less attractive as a distributor with a lower speed limit and cycle lanes.

The photograph below is of a distributor road on the edge of Kloosterzande where the use of cycle lanes only occurs within the town limits where the speed limit is reduced to 50km/h. This has been mis-applied in the UK on roads which are far too busy for mixing, but works here because the wider network approach means this is a relatively quiet street by UK standards (the town is bypassed). There is a tension between the road providing a connection function with the exchange function of an access road. Grey roads are very tricky to deal with and local context is very important.

Bio(mechanics) is about how the human body is affected by a collision and through road and street design to develop a layout which recognises this. The following is a summary of how this looks;

In other words, for each condition, this is the maximum traffic speed appropriate in terms of surviveability if there were a collision. The 50km/h (31mph) speed is interesting because it essentially requires people walking and cycling to be separate from people driving and it's the default Dutch urban speed limit. It also suggests that the road could be a distributor road (non-motorway). The 130km/h (81mph) speed limit is the motorway limit, although in places it's lowered for road layout, congestion or weather reasons.

The other implication of biomechanics is that we generally need to separate walking and cycling space because of the risk which people cycling at any reasonable speed create for people walking. This is a simplified explanation because there are subtleties between urban and rural places, but the principle of separation where speed differentials are high and integration when they are low is a fair summary. Throw traffic flow into the mix and you can see where decisions need to be made.

Psychologics is about is about ensuring that road layouts align with the general competencies of the road user, that they are ”self-explaining”, consistent and that people can adjust their behaviour depending on the prevailing conditions, especially older people. It does include an element of training people and potentially vehicle technology such as intelligent speed assistance.

For example a wide, multi-lane road suggests to someone driving that they can drive quickly, regardless of the posted speed limit or a narrow, confined layout with access for parking, trees and other street features is a place to drive slowly, regardless of the speed limit.

Here's a UK example (below). This street is 14.9m wide with a 9m wide carriageway tells drivers that this is somewhere where they can drive fast, despite the 30mph speed limit and that non-motorised users will only be people walking, keeping to the footways. The fact that there are houses on both sides is almost lost on the user.

The Dutch street below is roughly the same width, but the carriageway of around 5.5m with cycle tracks on each side tells a different story. In terms network of hierarchy, the UK street should be an access road and the Dutch street is a distributor road. Of course, if we decided that the UK street should also be a distributor road then under sustainable safety, we'd be providing cycle tracks and other features to protect walking and cycling. It all depends on how the network has been thought about and classified.

So we use a street layout to explain to drivers what to expect and we then ensure that all streets of a similar function look broadly similar so that an access road looks like one and a through road looks like one; no matter where we encounter them. The comment about older people is one where we should expect our reactions to be worse as we get older.

Responsibility ultimately sits with decision makers and designers - the people responsible for the road system and the same people responsible for making sure it is safe. It's a concept which should shame many in the UK, especially people who design a road to "standards" and then blame user for crashing. The Dutch approach states that ultimately, it is the national government which has overall responsibility for a casualty-free road system.

The UK approach tends to leave it up to local highway authorities and that is why we don't have decent national standards for highway design (other than for trunk roads and motorways). I think it is a stark comparison and suggests that at a national level, the UK only values people who drive on motorways and trunk roads.

Of course, individual responsibility to behave correctly is part of the equation, but even here, the planners and designers of the system are responsible for ensuring that layouts are forgiving and that people getting things wrong shouldn't die; or people shouldn't die from others getting it wrong.

Vehicle manufacturers have responsibility for the safety of their vehicles and indeed the idea of responsibility extends into social responsibility. For example, a pub chain should discourage patrons from drink driving (maybe even walking and cycling when drunk) by offering alternatives to alcohol (dare I say by making soft drinks much cheaper). Employers promote safe behaviours through staff development and company culture.

Learning and innovating is around the continuous improvement of organisations and professionals. The sustainable safety approach uses the Deming Cycle of "plan, do, check, act". The process is described as follows;

"It starts with the development of effective and preventive system innovations based on knowledge of causes of crashes and hazards (Plan). By implementing these innovations (Do), by monitoring their effectiveness (Check) and by making the necessary adjustments (Act), system innovation ultimately results in fewer crashes and casualties."

The Dutch investigate all road crashes where someone has died in order to learn lessons and where possible, extend this to crashes where someone has been seriously injured. It includes looking at data for trends or commonalities which can include the road layout, vehicle defects, behaviours or any other relevant issue. The objective is to learn rather than blame.

The dissemination of good practice is vital as well as embedding good practice into organisations so it becomes a core part of "business as usual" for everyone rather than relying on key individuals. This extends to municipalities, consultants, motor manufacturers and indeed anyone who influences the system.

Conclusion

Sustainable safety is a fascinating approach and the more you read about it, the more you can see its benefits. You can also see how badly the UK approaches the management of its roads and streets. The Netherlands and the UK have both built an extensive road network, including the bypassing of villages, towns and cities, but we then diverge. The Dutch have capitalised on this by redesigning their places for people whereas the UK largely hasn't.

The foundations of sustainable safety do have roots in the development and expansion of roads for motorisation and with the decisions on what each road is for. To some extent, it remains an approach coming from a driving point of view. It's probably not a surprise that the country has developed separate cycling and driving networks which just happen to coincide from time to time.

The lesson the UK can take from this is that we should be thinking about our highway networks first before we make changes whereas we often just look at a street or route in isolation. It is a concept which is at the heart of low traffic neighbourhoods where it is no longer acceptable to have local streets performing a distributor or through road function.

Equally, it forces us to think about those main roads in terms of protecting people walking and cycling. It also shows how difficult it is to deal with high streets because if we want to maintain the flow function, there are implications for how the street looks and feels; plus how easy it is to cross. In many cases, the thing that has to give way in my view is on-street parking, but that's another discussion!

No comments:

Post a Comment