I have spoken about cycle streets at the Active Travel Cafe, but it's a subject I think is worth exploring long hand in a blog post.

In fact, there are quite a few subjects I have spoken about there which I will write up here in due course, but let's start with cycle streets. The first question is of course what are they, and to answer this the best source of a definition is the Dutch Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic:

Bicycle street is a functional concept. It is a residential road for motorized traffic that forms part of the main cycle network or bicycle highway, and which is identifiable due to its design and layout, but has a limited volume of car traffic and that car traffic is subordinate to the bicycle traffic.

If we want to pull this together into some key design principles, then a cycle street should be;

- A main cycle route,

- Residential (the Dutch do sometimes use them in city centres),

- Where through motor traffic has been removed,

- An obvious section of a main cycle route,

- Where cycle traffic flow is much higher than motor traffic.

In addition, the cycle street's importance as a cycle route should be evident to all users and it should be designed and constructed to a high quality.

Cycle streets should also be designed so the cycle route has priority, and in the Netherlands this means local right of way rules are changed. In the UK context, this isn't so much of an issue, but priority is more than painting a give way line, it should be design priority which is self-explaining.

What we are trying to achieve as we always should be for cycling networks, is a cycle street that is coherent, direct, comfortable, safe and attractive. In delivering to those five requirements, the Dutch guidance pulls together some important considerations.

- 30 kp/h (20 mph) speed limit,

- Residential within or outside of built up areas (e.g. villages),

- One or two-way for general traffic,

- Cycle flows are greater than or equal to car flows,

- Cycle flows are greater than or equal to 1,000 cycles/ 24 hours and/ or if car flows less than 2,500 PCU/ 24 hours,

- If cycle flows are double that of car flows, then car flows must be less than 2,500 PCU/ 24 hours.

This essentially places an upper limit of 2,500 vehicles per day expressed as Passenger Car Units which weights for larger vehicles. If we want to convert this to a peak hour flow then broadly this might be between 10% and 15% - I say might, because this can vary by location. Essentially this is a maximum peak hour flow of 375 vehicles/ hour which could still feel quite high to some people and so the aim is to get those flows as low as we can.

Another important point to reiterate is a cycle street will be part of a main cycle route which means the approach needs to be appropriately deployed and so we must also be wary of creating what might appear to residents as rat runs for cycles. Although we aren't creating noise and air pollution problems, there is a risk that we make a street harder to cross. This is why we need networks and not sparse routes so that even cycle flows aren't heavily concentrated in one place.

We'll come back to some examples shortly. There is nothing to stop us using this technique if we follow the principles. Let's pause a second though. The photograph at the start had a Dutch bicycle street traffic sign. In fact it has no legal standing in the Netherlands and so the design response is far more important than a sign. The photograph above is Schützenallee, Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany which does have legal standing as a cycle street that features a whole list of requirements including having regard for the needs of motor traffic.

Schützenallee is a short cul-de-sac which has bollards creating a filter, but apart from traffic signs and large blue blocks of colour on the ground, there really isn't much in the way of the design led approach that is key to the Dutch experience. The UK can and should go the design route rather than the rules route because if traffic signs worked, we'd have no problems with drivers speeding.

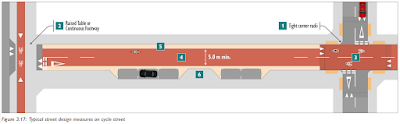

In terms of actual guidance, the UK experience varies. In Cycling by Design, Scotland has some level of detail which is inspired by Dutch practice (which we'll look at shortly). Page 91 provides the helpful sketch I've reproduced above and it states;

Where cycle volumes are expected to be high on mixed use streets, consideration should be given to the creation of a ‘cycle street’. The purpose of a cycle street is to convey a sense of cycle user priority within a mixed street environment and for motor traffic to be treated as ‘guests’ within this environment.

It also pulls out some key points which echoes the Dutch approach;

- Cycle traffic volumes are expected to be higher than motor traffic volumes,

- The street forms a key part of the wider cycle network and is expected to maintain high cycle volumes over time,

- The street does not form a through-route for motor traffic and is expected to maintain low motor traffic volumes and speeds over time.

It falls short of putting any numbers forward. On the one hand, prescription can lead to designers deciding not to take something forward if they feel a target can't be met (traffic flow in this case). On the other hand, not having some sort of numerical guidance risks specifying a treatment where it's not appropriate.

Wales does better in the Active Travel Act Guidance, where in Section 9.2.2. it states;

In areas where separation from motor traffic is unfeasible, it may be possible to improve conditions by removal of through traffic along the route or other appropriate traffic calming means, such as via modal filters, quiet street or cycle street provision (see Appendix G, Design Elements DE205 & DE206).

This can be particularly beneficial for residential areas where access by motor vehicle is still required (e.g. for residents, emergency vehicles and refuse vehicles).

More detail is given in Section 11.10 and drawing DE206 (above);

A cycle street is a quiet street which also serves as a primary cycle route. To succeed it should carry low volumes of motor traffic (under 2,500 AADT), and high volumes of cycling that significantly exceed motor traffic levels, to provide cyclists with a level of comfort comparable to that provided by a traffic free route.

The Welsh guidance also specifically separates the cycle street concept from what might just be a quiet street which is an important distinction as the latter won't be part of the main cycle network.

England is served poorly in guidance terms. Local Transport Note 1/95 Cycle Infrastructure Design in Section 14.3.27. misses the point somewhat:

Although the minor street network should all provide good cycling conditions it may be appropriate to designate some streets as important cycle routes, for example those which lead directly to an off-highway route through a green space. These ‘cycle streets’ could be indicated through changes in paving material, planting or other design changes so that they are understood as being principally for cycling.

In theory a green space might be useful, but from a personal safety point of view it's unlikely to be somewhere where everyone would feel safe at all times of the day and year.

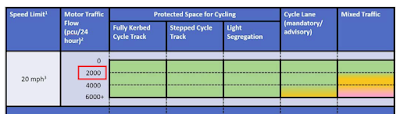

As we will see, design elements are important, but LTN1/20 seems pretty dismissive of what is a very useful technique. It is work looking at Table 4.1 of LTN1/20 however, because this does give us guidance on the conditions where most people will mix with traffic and that's a maximum threshold of 2,000 PCU at 20mph (see the extract above) and is 300 vehicles an hour at peak.

Between the three main pieces of UK guidance we can almost piece together the components we need to design cycle streets, but as you'd expect, the Dutch go into more detail which we'll now look more closely, referring again to their guidance which has three cycle street typologies.

First is "mixed profile" as can be seen above at Hoekweg, Voorburg (on the edge of Den Haag) which is one-way for motors. The design features given in section V12 of the Dutch guidance are;

- Asphalt or concrete surface,

- 4.5m wide to allow opposing flows or side by side cyclists to pass each other,

- Car parking off carriageway with a 0.5m buffer to the cycle space,

- Can have humps.

Second is "cyclists in the middle of the carriageway" as can be seen above at Verlengde Kerkeboslaan, Wassenaar which is two-way for traffic. It connects a pair of cycle tracks with the route passing through the edge of a very low density residential development.

The streets in the development are block paved, but the cycle street has smooth red asphalt making it clear that it is the cycle route. It is important to note that the strips at the sides are not cycle lanes, it is intended that people cycle to the left of them. The design features given in section V13 of the Dutch guidance are;

- Carriageway to to be red asphalt or concrete surface, 3m to 3.5m wide.

- Edge strips, 0.5m to 0.75m. Block paved preferred, black or grey.

- Car parking off carriageway with a 0.5m buffer to the cycle space.

- Side strips can be added.

- Can have humps.

The third is "carriageway separation and cyclists at the sides" as can be seen above at Havenstraat, Delft which is one-way for traffic. This design uses a central strip to create a pair of narrow strips which encourage cycling in the centre of each of them. The design features given in section V14 of the Dutch guidance are;

- Cycle lane to to be red asphalt or concrete surface, at least 2m wide.

- Central strip can be ridden on and 0.8 to 1.5m wide.

- Car parking off carriageway with a 0.5m buffer to the cycle space.

- Side strips can be added.

- Can have humps.

When cycle streets are used as part of a cycle network one can see the Dutch principle of "mix where possible; separate where necessary" in action. In the places I've cycled, cycle streets are just part of the changing scenery as one cycles between places on routes which will also have cycle tracks on main roads and which will also pass through residential streets, but where the route itself is seamless.

What is clear, is modal filters are very important such as above on Cromvlietkade which is the border between Rijswijk and Den Haag - the filter is the border! This is one of the main cycle routes between Leiden and den Haag. The main road feeding this street from the south only has painted (mandatory cycle lanes), but the turn into the cycle street is protected.

The cycle street part of this route passes through several modal filters before crossing a cycling (and walking) bridge over canal and which then forms a T-junction with a main two-way cycle track onto which a left turn soon brings one to the centre of Den Haag. It really shows how the motoring and cycling network are different things and how the treatments vary where they coincide.

Above is Hooikade, Delft, where a cycle street becomes a two-way cycle track. The cycle street is a two-way cul-de-sac for drivers needing to access residential streets. Proceeding ahead takes cycle traffic up a gentle ramp to a large road forming a ring road to the city centre, whereas a right turn drops the cycle track under the ring road to provide an alternative way to access the city, complete with a direct access to Delft Station (below).

Below is Noordlandselaan, 's-Gravenzande (near Hoek van Holland). This cycle route follows National Road 211 to the east, but as it approaches the outskirts of the built-up area, it diverts to provide a more direct route which doubles up as a residential access road which is filtered half way along. The greenhouse in the photograph is vast and is accessed separately. The edge strips here allow drivers to safely overtake side by side cyclists.

So, has the UK successfully deployed a cycle street? I only know of one example and that's the Taff Embankment in Cardiff which appears as a photograph in the Welsh Guidance.

The photograph above shows the central strip of the Dutch "carriageway separation and cyclists at the sides" (V14) approach with the strip being hard wearing light grey imprinted asphalt. So how does it shape up? On the positives;

- National Cycle Network Route 8,

- 20mph,

- Cycle lane strip 2.1m wide,

- Central strip 1m wide,

- Layby parking,

- Quality surface,

- Humps (at junctions),

The areas in which it doesn't quite meet the Dutch approach are that there isn't a 0.5m buffer to the car parking, the carriageway surface colour hasn't changed (although the central strip does provide a good visual cue) and there are no edge strips (although these are optional).

My understanding that the "cycle street" element was a bit of an add-on to the main purpose of the project which was a surface water flooding alleviation project, so it does perform a good secondary role. I haven't been able to find traffic or cycle flow data, but I suspect motor traffic flows are still a bit high because the area hasn't quite filtered out all of the through traffic which wouldn't be difficult given the parallel A-road.

So there you have it. Cycle streets are definitely a tool for the UK as we can apply a design-led approach, but it must be noted that these are network tools and not really for the delivery of single route treatments because we need secondary networks feeding primary networks.

.jpg)

The focus on motor traffic vs cycling volume is a concern that may give an excuse not to do anything.

ReplyDeleteCycling volume may be depressed because the whole council are is a cess pit for cycling.

I'd be more for sometimes simply modal filtering the obvious roads, as a quick and cheap answer.

Very much agree on road signs - my lane is "no traffic at all except for access" for 50+ years, and we are still plague by rat running taxis and delivery drivers.

It's why I go to pains about creating a network. Trying to do this on a single route is going to be very challenging and when being used as part of a network, the street treatment is also very important to convey the "cars are guests" message - filtering can get us a long way, but the Dutch examples I give are part of a dense network which also has cycle tracks on main roads and cycle tracks away from main roads.

DeleteCheers.

ReplyDelete