I had cause to dust down some of the older guidance and research on contraflow cycling in one-way streets this week and I think it's useful to throw it open to a wider audience.

The earliest reference I have for contraflow cycling is in the Bicycle Planning Book (1978, Mike Hudson) which has a drawing showing a mandatory cycle lane being used as a contraflow (below).

The layout uses a "plug" in the end of the street where cycle traffic can enter, but general traffic cannot. The plug is a traffic island where cycles pass left (there's a blue mandatory cycling sign) and general traffic has a no entry. At the other end cycle traffic gives way to the other main road.

Many "plugged" junctions you see look quite old fashioned in terms of space an accessibility. This is mainly down to the older traffic sign rules which did not permit a cycle exemption to the no-entry which meant the island with a cycle bypass was the only legitimate way to introduced such an arrangement. If you've some decent space, a plug is quite useful to stop drivers leaving the side road from cutting there corner where cyclists might be entering.

The photograph is another example of a plugged junction, although in this case the road beyond is actually two-way for all traffic and is so known as a "false" one-way. At a higher level, we've been able to do things like this a long time. Traffic Advisory Leaflet 8/86 (which I cannot find a copy of) was a case study of a plugged junction in Meymott Street, Southwark. This is now just a piece of history as the junction has been fairly recently changed to a "no entry except cycles" arrangement.

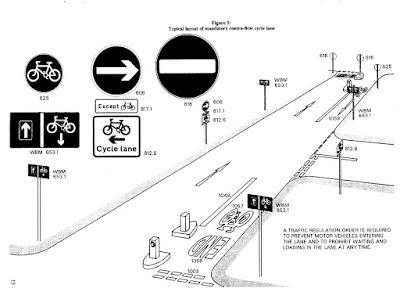

Traffic Advisory Leaflet 1/89, Making Way for Cyclists, includes a diagram of a mandatory contraflow cycle lane (below) with some accompanying commentary. Interestingly, the contraflow one-way sign is referenced as "WBM 653.1". This is a variation of diagram 653 which was the reference of a contraflow bus lane at the time. WBM means "Worboys series B - Metric" with Worboys being the commission with standardised UK traffic signs. In other words, it wasn't a standard sign and would have to have had a traffic authority make an application to the DfT for a Special Authorisation to use it. In other words, more work to provide for cycling.

It's often hard to find early guidance (at least online), but in 1996, Cycle Friendly Infrastructure was published by the Bicycle Association with the Cyclists Touring Club (now Cycling UK), the Institution of Highways & Transportation (now CIHT) and the Department for Transport. There was an guide from IHT in 1984, but I've so far not found a copy. The sketch below is of a plugged junction and the text which accompanies it says;

11.4.1 Advantages and disadvantages. Cyclists can be seriously disadvantaged by one-way streets. They Introduce additional distance, delay and often hazards at intersections where weaving and non-standard road positioning is required. Vehicle speeds also tend to increase. Arrangements that permit cyclists to use streets in both directions can redress this situation and give cyclists a positive advantage over other traffic. The need for contra-flow arrangements will sometimes be apparent from cyclists disregarding one-way orders.

The safety record of contra-flow lanes and other arrangements is generally good as there is good intervisibility between cyclists and oncoming vehicles (Werele 1992). A conclusion of the European Greening Urban Transport project, based on the experience of many towns and cities, is that in almost every case it is possible to exempt cyclists from one-way street regulations.

11.4.2 Contra-flow cycle lanes. A contra-flow cycle lane should ideally be at least 2m wide, but where road widths are restricted it can be a minimum of 1.5m. A mandatory lane is marked by a solid white line (1049) with signs (960.1). Waiting and loading restrictions on the contra-flow side are needed. If this is not possible, parking /loading bays should be marked and width should be allowed for car doors opening.

A coloured surface is desirable. The with-flow lane may be as little a 2.5m wide depending on factors such as traffic volume, speeds and goods vehicles. In circumstances where oncoming vehicles may occasionally need to encroach on the cycle lane to pass parked vehicles, an advisory contra-flow lane may be used.

The first paragraph of the text is key because where we want to enable people to cycle, we should be making every street possible accessible and so a combination of one-way loops for general traffic and two-way for cycling can both remove through traffic to make streets quiet enough for people to just cycle in the carriageway, but not to the disadvantage to maximum cycle access. (The text is essentially what TAL 1/89 was saying).

Contraflow cycling on a German street

In 1998, the Transport Research Laboratory (now TRL) undertook some research into contraflow cycling provision in its Report 358, Further developments in the design of contra-flow cycling schemes. The research looked at several existing sites which had varying conditions and through the use of video analysis and interviews with cyclists sought to try and put some numbers into what works. The executive summary says;

Contra-flow cycle schemes have been operating satisfactorily in the UK for many years. Most of these involve a mandatory contra-flow cycle lane and segregation at the entrance and exit. However, the number of contra-flow schemes installed has been quite limited, particularly when compared with certain other European countries. This appears to be due to the difficulties of implementing conventional contra-flow schemes, and a largely unfounded belief that contra-flow cycling is dangerous.

Some of the sites used the "no motor vehicles" restriction at one end of the contraflow systems which is slightly odd, but I think these situations didn't have enough space for plugs. I'm not quite sure on the prevailing legalities of the time, although the report does talk about Special Authorisations. It probably doesn't matter too much as some of the locations are so narrow, drivers can only travel one-way anyway.

The conclusions from the research are manifold and so it's worth having a read yourself, but for me, the following are most eye catching;

- Many cyclists travelled illegally against the one-ways prior to the schemes being implemented and after that, cycle traffic grew.

- There was no evidence of cyclists being put into significant danger by drivers.

- Motor traffic flows and speeds were generally low, but excessive speed was a concern of cyclists (subjective safety in other words).

- Even under the illegal behaviour scenario, there were no casualties amongst cyclists for 15 years before schemes were implemented and none recorded after.

- Cyclists generally felt safe and this was in all types of situations of narrow carriageways, all sorts of kerbside activity, high numbers of pedestrians and with low and high cycling flows.

From a policy point of view, the general suggestion is essentially roll it out everywhere, including places which gives cyclists an alternative to hostile gyratories and roundabouts. In terms of numbers, TRL suggested;

- Traffic speeds over 30mph or flows over 1,000 vehicles a day will generally need segregation.

- Low traffic speeds and flow make this approach good from a cost, aesthetic and practicality points of view.

- It works in narrow streets (or effectively narrow streets - i.e. space taken by car parking). Even short sections of 2.5m wide work fine.

- Cyclists and drivers are looking towards each other and although driver speed might need managing, this is a good safety feature.

- Drivers coming out of side streets and not realising there is two-way cycling is the greatest safety risk.

- Parking and loading can be an issue and might need managing.

- Cyclists preferred clear signage and road markings.

There is also a Traffic Advisory Leaflet which summarises this research; TAL6/98 Contraflow Cycling. The TAL refines the advice a little and gives more nuance (and much more advice). Some key options are;

- Mandatory cycle lanes are needed if protected space is needed for cyclists at all times and where parking and loading is banned and where drivers won't be encroaching into the lane.

- No cycle lane is needed if 85th percentile (driver) speeds are under 25mph and vehicle flows are under 1,000 per day; or the street forms part of a 20mph zone.

- Advisory cycle lanes are needed if either 85th percentile (driver) speeds are under 25mph or vehicle flows are under 1,000 per day

We then fast forward to 2016 where we have the Traffic Signs Regulations & General Directions 2016 which finally do away with the general need for plugs because we now get a "no entry, except cycles" exemption (below) which is much more in line with many other European countries.

Of course, the "no entry, except cycles" isn't going to be appropriate everywhere, but it is a useful tool.

Finally, in 2020, Local Transport Note 1/20 Cycle Infrastructure Design was published by the DfT and Section 6.4 talks about contraflow cycle lanes. This is slightly confusing because the advice on contraflow cycling without lanes is elsewhere and maybe contraflow cycling as a subject could have been kept together. The key paragraph for contraflow cycle lanes is;

6.4.23 Contraflow cycle lanes should normally be mandatory, although an advisory lane may be considered where the speed limit is 20mph and the motor traffic flow is 1,000 PCU per day or less. The entrance to the street for cyclists in the contraflow direction should always be protected by an island to give protection against turning vehicles (see Figure 6.25) where traffic speed and flow is higher.

For situations without lanes, Section 7.3 covers it and suggests;

7.3.4 Permitting contraflow cycling in one way streets and using point closures to close certain streets to motor vehicle through traffic will generally provide a more direct route for cyclists and should always be considered. On quiet low speed streets, there may be no need for a cycle lane (see Figure 7.4 and Section 6.4), enabling cyclists to use narrow streets in both directions. Where there is good visibility cyclists and on-coming drivers should be able to negotiate passage safely. Contraflow cycling should be signed in accordance with the advice in the Traffic Signs Manual.

The Scottish Government's 2021 Cycling By Design document also covers contraflow cycling, but it seems more cautious than LTN1/20 and gets a bit more prescriptive on general traffic lane widths and not really anything about not having cycle lanes. for example, the guidance suggests a general clear traffic lane width of 3.0m to 3.2m. Once you introduce a cycle lane (say 1.5m to 2.m), the implication is going to be that in many situations, car parking is going to have to be cleared out.

A narrow street with car parking on both

sides with contraflow cycling

In my view, both sets of guidance miss the TRL research nuance (LTN1/20 in terms of structure, but most especially the Scottish guidance) and inexperienced designers will miss some of the site specific issues. This risks situations where the guidance will be used to "show" that contraflow cycling cannot be used in a situation were the alternatives are those situations TRL are saying they can avoid. The other point to make here is there will be plenty of streets in the same town or city where such discussions are had which still allow two-way driving!

The Welsh Active Travel Act Guidance, 2021, also covers contraflow cycling and has nice data sheets in Appendix G which sets out criteria, dimensions, flows and useful tips for segregated contraflow cycle lanes and unsegregated contraflow cycling. For my mind, this might be a little more helpful for inexperienced designers.

For me, I think the general approach for streets which are not gyratories or dual carriageways should be to have 2-way cycling by default. If there are situations where there are speed and/ or volume issues, then start adding the engineering which could be filtering (which is probably the right approach in many cases) and then cycle lanes or tracks which might need parking and loading dealing with.

One of the best approaches I have seen is in the London Borough of Lambeth. The council commissioned research to look at its one way streets to see how they could most practically made 2-way for cycling. Based on a series of attributes, the consultants proposed five categories of street;

- Group 1 – No formal cycle lane required.

- Group 2 – Segregated contraflow cycle lane advisable.

- Group 3 – Mandatory contraflow cycle lane advisable.

- Group 4 – Advisory contraflow cycle lane advisable.

- Group 5 – Two-way cycling not advisable.

The idea was to take this output and use it for a programme of upgrades to enable 2-way cycling as much as possible. Interestingly, the list of Group 5 streets were just three. Two were extremely narrow and one would have had an "unacceptable" loss of car parking to make it work. The really narrow one, Randall Row, could actually be pedestrianised in my view!

The lesson from Lambeth and other places which have seriously looked at this issue is having a logical and systematic approach is a good one and even if all one-way streets cannot be made 2-way for cycling immediately, there are probably very few situations which cannot and maybe they are the ones needed more detailed consideration. In any case, the technique has been with us for over 40 years and so is nothing new and shouldn't be contentious.

Thank you, thank you - GoBike in Glasgow has been hammering at Glasgow City Council about permitting contraflow cycling whenever they introduce yet another one-way system in parked-up residential streets. There are official statements supporting the idea, but in every specific case it proves to be impossible because of 'police advice' of which a copy is never available. We had hopes of the new CbyD, but no dice. Hoping the council's new Active Travel Strategy (nearing the end of the consultation period) will find the guts to be dogmatic about permitting contraflow.

ReplyDeletePolice Scotland's comments will be subject to Freedom of Information; if they cannot produce it, then it doesn't exist!

DeleteI am confused by the section in LTN 1/20:

ReplyDelete6.4.21 There should be a general presumption in favour of cycling in both directions in one way streets, unless there are safety, operational or cost reasons why it is not feasible.

Does this refer to the Highway Authority, or the cyclist. Lack of clarity is concerning with the proposal to allow Local Authorities to levy penalties for going the wrong way down one-way streets.

That's for the highway authority. I'd maybe go so far as they have an obligation to review what they have, but that's to be tested in court I guess.

DeleteContraflow cycle lanes are prohibited by Vienna convention on road traffic. That is why in the Netherlands they are not used. What you see on the signs as „except bicycles“ is the way they move around this requirement.

ReplyDelete