A very common design feature of Northern European streets is where footways and cycle tracks have their levels maintained across side streets. There are of course lots of different ways to do it, but the principles count.

The photograph below is a main road in Malmö, where there is a stone sett buffer area between the cycle track and the carriageway. The cycle track is "stepped" up from the carriageway and the stone setts are ramped as it passes the side street.

The photograph below is from Billund, Denmark - the home of Lego. This example uses a little hedgerow as a buffer, but the continuous nature of the footway and cycle track is absolutely clear at this access.

These are all nice and pretty obscure examples to demonstrate how common this is, but it is of course no surprise that the Dutch have taken this to the next level.

The photograph below is from Amsterdam showing great example of all of the little bits of detail working together to keep priority with those going ahead. In fact on this street, priority for those going ahead is set within the traffic laws, but actually the design does the work.

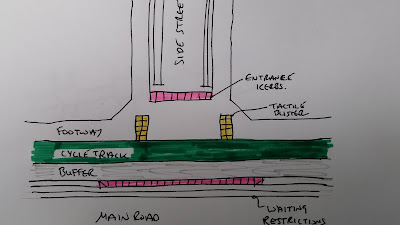

The photograph above shows the left hand and right hand transition units with two ramp units set up in the centre. This is the version of the product which fits with British Standard half-battered pre-cast concrete kerbs (HB2 for the nerds). For lots more detail, have a look at this post from just over a year ago. The sketch below shows how the units (in pink) fit with the wider layout of a side street.

Here in the UK, we have struggled with these principles, but actually they have been here all along. Ignoring the cycle lane in the photograph below, we have a continuous footway with a buffer. The change in level is dealt with in the buffer area and the turn in and out is tight. Every so often you'll see nice little UK examples of this approach on social media.

The problem I find in the UK is that the principles are not well known among designers. In some places such as Waltham Forest (below), a conscious decision has been taken to roll out a consistent detail, although perhaps having to rely on paint to reinforce the layout isn't quite right.

As you will have guessed from the title of this post, I have just gone around the houses a bit. Of course, this is about showing you that we now have a real life version of the type of units the Dutch have been using for years with the first shipment about to head out into the wild from Charcon (part of Aggregate Industries).

The interesting behind the scenes thing is the first units were going to be a square profile version in a stone effect finish for a scheme in Salford, but in fact, the first UK scheme to use them is the Coundon Cycleway in the UK's Motor City of Coventry where lots of standard materials are being used. It is also worth mentioning that the scheme is also using a 30° kerb between the cycle track and the footway. This is new cycleway will be a smorgasbord of design principles promising to be one of the best in the UK. Do follow Peter Howarth, the scheme's project manager, on Twitter to see photos of the scheme emerging and all credit to him for putting faith in the product.

This has been a bit of an obsession for me ever since I had my first chat with the technical people at Charcon around the concept and why it could help in delivering continuous side street treatments. I do need to give a hat tip to Catriona Swanson who got Salford City Council discussing the product with Charcon because it needed a decent sized project to make the development of the product viable from a research and development point of view.

I also need to give a hat tip to Adam Tranter, the Bicycle Mayor of Coventry (among other things) who got me and Peter Howarth discussing the the units. What this has shown is once a few people see the value of a good idea, it can take a life of its own. Charcon tell me that they have had orders for the product from the Isle of Man and they are getting a steady stream of enquiries from designers and specifiers.

I can't wait to see the first units going in, even if it has to be from afar at the moment. At last 2021 sees another piece of the jigsaw becoming available to us.